I used to teach mixing and would get annoyed when I’d use the terms hard and soft limiters with audio engineering students… and they would look at me with blank stares as if I were speaking a foreign language. So for the sake of reducing my general annoyance level, here’s some information about mixing using limiters, and what sort of impact on your sound that you can get with a hard vs. a soft limiter.

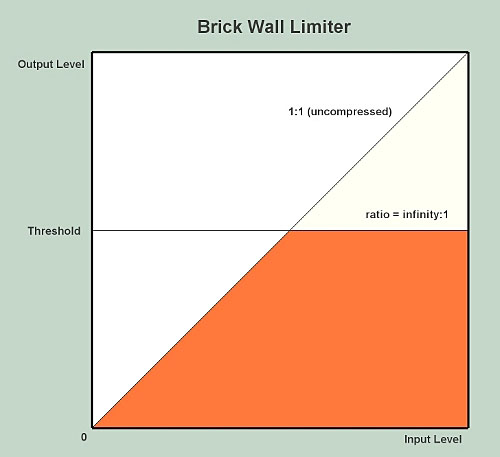

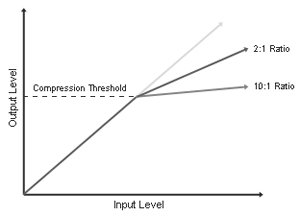

First: A limiter is generally defined as an audio compressor with a ratio setting at least 30:1; basically so the gain reduction curve is not so much a curve as it is a 90-degree turn that creates “a brick wall” over which the level cannot go. For that reason, I tend to prefer looking at limiters more like brick walls or dirt floors (infinity :: 1 ratio) rather than just an extremely tight curve and sharp knee.

Hard vs. Soft Limiter Settings

To visualize the sound: one is like hitting concrete wall with a metal baseball bat (hard limiter), and the other is like hitting dirt ground a tree trunk (soft limiter). Both stop movement very quickly, but the first couple milliseconds of impact, coupled with what happens after impact (i.e. does it instantly bounce back or not) is what makes the difference in how each sounds. Read on the visual will start to make more sense.

- A hard limiter has a fast attack time and a fast release time, whereas;

- A soft limiter has a (relatively speaking) slower attack time, and much slower or longer release time. (The slower release time effectively results in the limiter always attenuating the signal to some extent so that there is less breathing resulting from the limiter disengaging and the make-up gain therefore boosting the signal louder than the original input level.)

Knowing the settings for a hard vs soft limiter is one thing… knowing what is sounds like is another – and what knowing what it sounds like is the important part.

Knowing the settings for a hard vs soft limiter is one thing… knowing what is sounds like is another – and what knowing what it sounds like is the important part.

Hard limiter settings tend to have an industrial feel to them. Hitting an aluminum bat against a giant metal building. HARD. An instant stop of dynamics has a particular feel and sound to it that we not only hear, but can sense. People can almost feel it physically like being slapped in the face. Industrial sounds also tend to have a resonance to them that feels a bit more metallic; a lot of resonance stuck in a small dynamic range.

One aspect that is often overlooked insofar as why the output sounds the way it does when setting dynamic processors is the OUTPUT gain, which you generally boost to compensate for the signal attenuation. In the case of a hard limiter you are getting an awful lot of gain reduction, so therefore set a lot of output gain to compensate. The output gain compensates, but you also have to think of it as if the gain reduction achieved by your attack and release settings are somewhat fighting against the output gain – pushing and pulling in opposite directions. When your settings create an epic struggle, then you get lots of breathing and “pumping” from your compressor / limiter.

Fast attack and release on a limiter: Having a really fast attack and release means the signal’s attack gets squashed hard core, then the limiting (signal attenuation) is quickly released, which means the quieter parts get turned up a lot because of the output gain… the result is a massive increase is the total resonance of your signal.

The best example is with a snare drum. Put a hard limiter on a snare drum and the thing will ring like there’s no tomorrow. The ring is the resonance of the snare that was originally lower in relation to the stick hit. Due to squashing the attack (the stick) coupled with the make up gain that boosts everything else, a hard limiter makes the resonance a lot louder in relation to the whole signal – so much so that sometimes you get a sort of “boing” sounding snare drum.

Using a hard limiter on a snare as a parallel approach can sometimes be interesting when mixing your song. Double the snare track, put a hard limiter on one, then blend it with the original signal to stabilize the dynamics, as well as augment some of the more subtle tones inside the instrument that are more difficult to hear in the mix. If you watch your phase and don’t overdue it, that can help bring more life and dynamic range stability to different instruments without any “over compressed and therefore flat” sound.

Soft limiters, since the release time is long, do NOT effectively increase the resonance to that degree because the limiter is still engaged after the peak of the attack – it’s still “limiting” when the resonance happens (attenuating the audio signal), so therefore it doesn’t get louder by the make-up gain. This squashes ALL of your signal rather than just the attack, which means you don’t get the resonance increase.

Soft limiters can work for when you don’t want tone to change, but for instruments or signals that are only in stereo fields (you can “hear” limiting more if it’s mono or mixed evenly in both Left and Right channels, and less if it’s panned more towards either side). It will increase the RMS of your mix so for stacks (vocals, guitars, etc.) it can help to blend them in to give it more perceived power.

OK. Now go play.

Note: remember to be very careful when limiting. You can go way too far, way too fast and your mix will sound terrible. Practice going too far at first so that you get to know how it sounds, then reset everything and start over. Thereafter, try working it in as a type of parallel compression when your mixing your tracks so that you get more power in your mix, but don’t hear the squashed dynamics too much.

Published: by | Updated: 08-11-2014 14:17:04